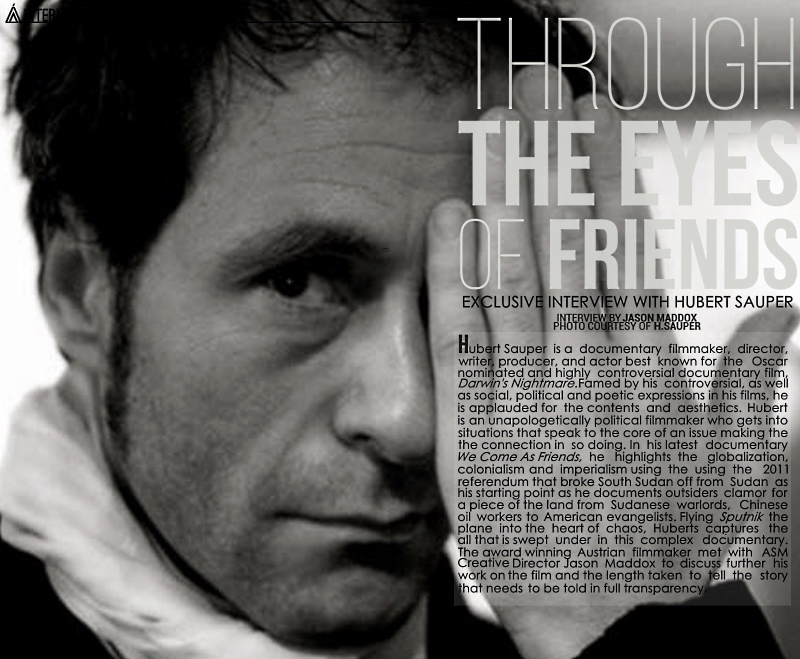

Through the halls of ASM’s current headquarters, he stops to reflect. “Why didn’t you tell me that you exist?” “That this place was here?” You would never know it from outside. Much the same could be said of the man before me; in athletic shoes, a suit jacket and jeans. With lightly guarded gaze under his furrowed brow, he shakes my hand and then his eyes begin to trace the seams along the walls in the hallway. He takes a reflective pause and then begins immediately. “I think film is like architecture. We have to build things carefully; and the things we build tell us who we are.” Hubert Sauper strikes me as a sincere man. A man who when in Europe would gaze into the eyes of strangers and would see bold questions of origin that would lead him to spend a great part of his life as something of an outsider himself observing whose curiosity and fraternal sympathies have led him through some of the most fricative fault lines of changing Africa as women and men build their lives at the intersections of timeless community and sometimes craven forces driven towards exploitation from outside.

ASM: You have spent many years of your life making films in Africa, first in Congo and now in Sudan and South Sudan visiting many people on the front lines of the changing world. Has this process changed you personally in any way?

HS: I feel like I am more of a complete European. Africa is the other part of me because it is so interconnected through migration and thousands of years of cultural exchange. Larger African civilization spread through Egypt and into Greece and through Europe. Connecting with the source has made me feel more complete.

ASM: Your work seems to speak

to a friction in this unity. How do these two sides of

yourself reconcile themselves intellectually?

HS: Europe has a dialectic with Africa. They have

a very interconnected relationship like the Americas

North and South. The relationship has always been over

the centuries unbalanced obviously. It has been

unbalanced in terms of resources and in terms of power.

It is a total disequilibrium. What is also out of balance

is the narrative around the situation. The narrative is

that Africa needs help and we have to “come as friends,”

which is the title of the film. But the truth is that

Europe needs help. Europe gets all the wealth out of

Africa; so actually Europe is being developed by the

wealth, the workforce and the resources of Africa. From

the land and all of its richness in oil, gold, diamonds,

coltan, uranium - you name it. I live in France and you

know Paris is called the City of Light. It is lit up by

uranium, which of course comes from Africa, that’s it.

So, the narrative is the wrong way around. We are saying

we should help Africa, and send some wealth to Africa,

but you know the truth is that Africa is helping everyday

and every night. It is helping Europe to be wealthy to

such an extent that it is inconceivable. It is kind of an

incident of cognitive dissonance that you cannot conceive

that the actual truth is so much in opposition to what we

think is the truth. When we make a movie like this, a lot

of people react with disbelief as though this is not

possible. They get out of the movie theater in disbelief

asking themselves, “Did I just see what I saw?” “What is

this, because it is just so off and away from everything

we think we know?” But this is it. This is what I see.

This is the deal there is nothing else.

ASM: Is there a time when you did not see that?

HS: Well, yes but that was before I went to Africa. It is now almost twenty years ago since I first traveled there. One of the strange things for me was like destiny. On my first trip into Africa I arrived directly into a civil war without wanting to. I was in the Congo at the moment the war broke out that I could not at that time have foreseen the rebellion of the Congo when the dictator Mobutu was overthrown and the new dictator Kabila took over; now Kabila’s son is running the Congo. Basically 1997 was the big deal where the whole power shift in Central Africa started to pivot and I happened to be there with my girlfriend. We were stuck and could not get out, and I shot this movie which was traumatizing. You have to have a very good day to see it. The thing is that I did not just show the genocide, because many people do that. What I did was basically show as a filmmaker, the fear, the confusion and the anger that you have witnessing such a thing. In all my films, I think the most important thing is not what you see as the movie but what is behind it. When you see a movie like this you can be with the person who films it. You can understand that this person is interacting with the people in a very direct way; and not like the BBC, CNN or newscasters who have a short time to break the news and do not have time to interact with people. They need a story that has simple factual reporting.

ASM: How did this initial film

come about? What brought you to the Congo in the first

place?

HS: I was going to do a documentary on

refugees from Rwanda. I asked myself a good question,

“what was I doing there?” Well, I was there to make a

film about refugees, but I was neither ready nor prepared

to make a film about refugees who are being chased,

hunted down and shot dead. However, I was planning to

make a film about refugees or the UNHCR; - a UN structure

concerned with refugees, who claimed they were looking

for Rwandan people who had fled to the Congo, which is

about a thousand kilometers away from Rwanda. What the UN

found along with me on this little trip into the jungle

were a hundred thousand people who were like living

skeletons. It was literally like walking into a camp in

1945 in Europe. It was exactly the same kind of image

that blew my lid. It was from then on that I knew I was

to either cut off the whole trip and never go back or go

back and figure out what was going on. You never find

out what is really going on but you can try to share

impressions and ask questions at least. Once people

realize that a trip has been made to Africa and they hear

of these stories, they often ask what they should do and

where can they donate. I do not have an answer because it

is so complex. However, I know that answers come out of

the fact that millions of people see these films thanks

to these people with the courage and vision to show them

(gestures to the BBC representatives) because many people

get to see the crazy reality and thrive to find answers

and debate. My film is a vector or vehicle to ask the

necessary questions.

ASM: It seems that you were caught off guard by the situation that gave rise to your first film in Africa. Was there a difference in your approach to your most recent film, compared to your first experience in Africa?

HS: Well, the first one was obviously not the result of a long reflection. It was more of a reflex. I had only two options; to look there or to look away or to document or not document. The situations were so deeply disturbing, that a lot of times I said I could not do it anymore. Ultimately, I think I made that first movie because I could not make the movie. I could not turn away and forget what I had seen nor could I simply say to some news source, “ok, here are some tapes.” I could not go on with my life without making this film. It was for me absolutely necessary.

ASM: Why film? Was there a deeper personal reason you chose to dedicate your time and soul to these projects rather than simply reporting these things to a political representative?

HS: There are important things in life that one simply cannot turn away from. Some things are so terrible that you have to communicate. For me it was as profound and simple as the answer to the question of why do we as human beings organize wedding parties or funerals. There are certain moments in life where you cannot be alone. You want to share your joy or your grief. If you see something terrifying happening in front of your door, such as an old lady getting run over by a drunken guy, you would not walk into a room full of your friends and say "hey guys, you want more coffee?" You will communicate what you have just seen and they will lend you their ears and listen to you because you do not want to be alone with what you have just seen. This is what artists do in general. They craft and edit these things that they feel or sense and formulate it into architecture, music, fashion, or cinema.

ASM: After all of these years of engaging with and reflecting upon the Congo situation, were you able to see the events in Sudan developing before things got as hot as they ultimately became?

HS: My time in Africa surrounding this last film We Come as Friends, has involved a lot of thought. It is a meditation on things that unfortunately I have seen over and over. Once you see things over and over, you begin to be able to pick out patterns, figure out connections. Making a movie is nothing other than putting things into certain perspectives, which I feel I am more able to do as time goes on.

ASM: So as a documentarian, your material is patterns rather than simple statements?

HS: A lot of scenes in We Come as Friends are on their own, not very relevant. A western ambassador giving a speech to locals is very random; but westerners usually say all of the same things. First they say the title of this film: "we come as friends,” “we want to be with you, we will help you to develop.” The unsaid part is “we want your oil and your gold,” which is written in between the lines of these statements. As a filmmaker, once you know these things and have learned your craft, you can start to represent these scenes in a way that allows you as a viewer to see in between these lines without me standing in front of the camera and saying "look this is hypocritical". If I do my job as a filmmaker, we can just let them speak into the context of a film in which the viewer is mentally and psychologically prepared to see and hear certain things in a way that is more highly attuned to what may have taken me time to learn firsthand. Seen in this context, an otherwise banal word becomes something akin to strike into your soul.

ASM: Would you say that your subject is this process or is Africa the subject of your films? Or is the subject specifically the problems of society that simply happen at this moment to manifest in Africa? Which are you more interested in looking at?

HS: Well, Africa is not the subject. The subject is how human beings create a narrative around what they do and why they do things. It is something born of all of my searching and wondering about the conditions of this gross inequity; this process of perpetual colonialism. It is however set in Africa - a place that has always been fundamental to our human story.

ASM: Was there anything beautiful beyond the obvious nobility in struggle to remain autonomous that struck you during your time with the people of your films?

HS: The young people in these villages are very connected to something very old in human history-older than any civilization we know. Often, you can feel the most profound and beautiful personal expression. A child will go out into their environment and find the things that resonate with them. They hold onto practices that evolve organically. But the devastating thing is that those who say “we come as friends,” do not appreciate this. Instead by way of historically unbalanced power relationships, they position themselves as though they are gatekeepers; putting the people in uniforms making them march in step to work and to change their beautiful spirit. Again, these are things I do not say directly in the film, but hopefully when you view it, you are able to feel that this is inhumane. There is something beautiful in the cultures they try to suppress.

ASM: Has the time you have taken on this in any way changed your impressions of these forces? And after all of this, have you developed a wish for those you know in the parts of Africa you have visited?

HS: When I first arrived in Africa twenty years ago, I was shocked to see things I never would have expected to encounter. But now upon reflection, I am able to approach my own feelings about a situation with a presence of mind that is more refined and can put visuals to experiences that previously before this reflection; I could barely stand to witness. Hopefully this allows me bring a truer picture to those who view my films. In answer to the second question, my wish is that we as a human family can learn to collaborate with dignity and respect. That Africa be allowed to develop in its own time and in its own ways. That we can learn to honor the connections that have existed for thousands of years by admitting that Europe needs Africa.